Published August 18, 2025

Reading time: 5 minutes

By Jordy Munarriz

Jordy Munarriz

Environmental Engineer with a master’s degree in renewable energy and a specialization in sustainability. A passionate traveler and advocate for responsible tourism, he captures the essence of exploration through storytelling, inspiring others to connect with nature in a conscious and meaningful way.

References:

[1] Holmer I. Protective clothing in hot environments. Ind Health. 2006;44(3):404-13.

[2] Havenith G. Interaction of clothing and thermoregulation. Exog Dermatol. 2002;1(5):221-30.

[3] Parsons K. Human Thermal Environments. 3rd ed. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2014.

[4] McCullough EA, Jones BW, Tamura T. A data base for determining the evaporative resistance of clothing. ASHRAE Trans. 1989;95(2):316-28.

[5] Gagge AP, Stolwijk JA, Hardy JD. Comfort and thermal sensations. Science. 1967;157(3787):1557-8.

[6] Rossi RM. Textiles and human thermophysiological comfort in the cold. Ann Occup Hyg. 2001;45(4):239-46.

[7] Richards M. The thermal manikin: History and applications. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2005;94(5-6):641-8.

[8] Bartels V. Physiological comfort of protective textiles. In: Scott RA, editor. Textiles for protection. Cambridge: Woodhead Publishing; 2005. p. 371-400.

[9] Lotens WA. Heat transfer from humans wearing clothing [dissertation]. Eindhoven: Eindhoven Univ Technol; 1993.

[10] Havenith G, Heus R, Lotens WA. Resultant clothing insulation: a function of body movement, posture, wind, clothing fit and ensemble thickness. Ergonomics. 1990;33(1):67-83.

[11] Li Y. The science of clothing comfort. Text Prog. 2001;31(1):1-135.

[12] Gonzalez RR. Biophysics of heat exchange and clothing: applications to sports physiology. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1987;19(5 Suppl):S162-70.

[13] Nielsen R, Endrusick TL. Sensitivity of the thermoregulatory system to changes in core temperature in man. J Appl Physiol. 1990;69(2):477-84.

[14] McQueen RH. Odor in textiles: a review of evaluation methods, fabric characteristics, and odor control. Text Res J. 2015;85(2):123-36.

[15] Chapagain AK, Hoekstra AY. The water footprint of cotton consumption. Value of Water Research Report Series No. 18. Delft: UNESCO-IHE; 2004.

Latest News

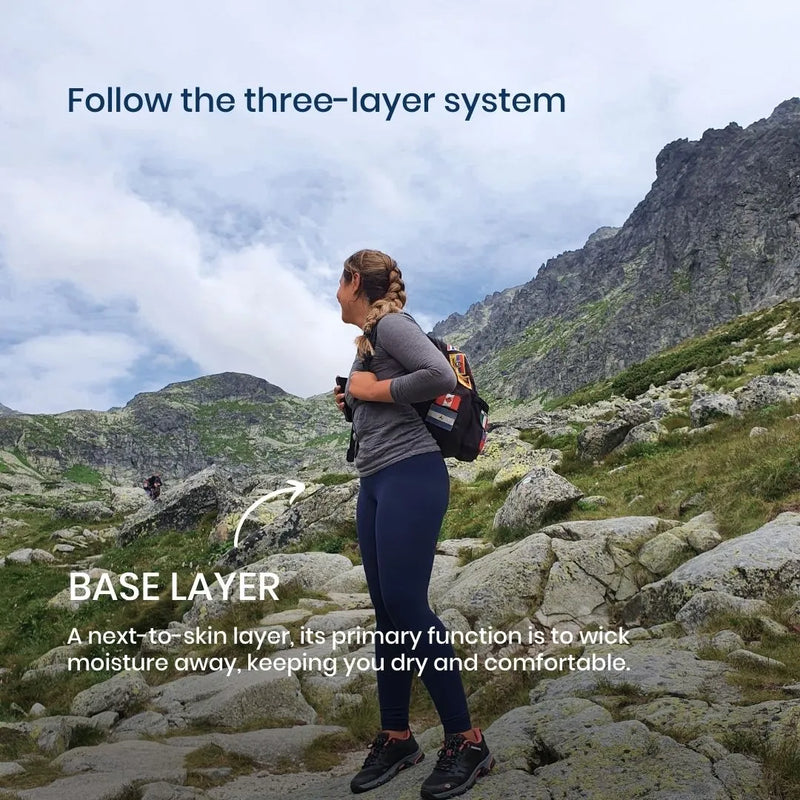

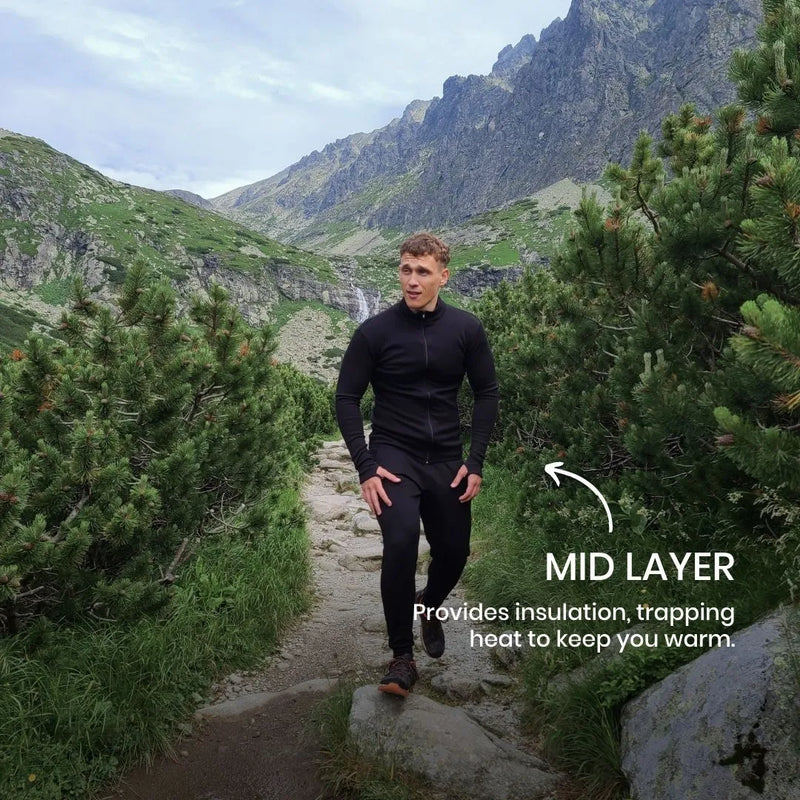

The Art of Layering Clothes: How to Layer for the Outdoors

Learn how to layer clothes for outdoor activities with base, mid and shell layers. Stay warm, dry, and comfortable in any environment.

Weaving Time: The Peru You Don’t See in the Picture

Explore the other side of Peru—where weaving, tradition, and the role of alpaca reflect a slow, intentional approach to fashion.

What Is a Micron In Wool Clothing?

Learn what a micron in wool means, how it affects softness, durability, and price, and how to choose between alpaca, merino, and cashmere.